Thursday, April 30, 2009

7pm Fort Wayne Time... 1am Buja Time

The low-flying plane gave us panoramic view of the city we grew up in. Downtown, our high school, our old neighborhood. Something about being in cities like Nairobi, Brussels, Chicago, that makes the announcement, “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome of Fort Wayne,” a bit underwhelming. But we sigh the sigh of total familiarity and gratitude, because it’s always there for you, your hometown.

Off the plane and through the terminal, and there they are. The ones who spent Christmas without us. And wrapped up in the reunion, the exhaustion of travel evaporates into clouds of celebration. The potential for time together sates our souls, and we know we have no goodbyes to say for a while. I’d love to go into deeper descriptions of the airport, my pleasant drive through the city in my car, and the rest of the afternoon, but those clouds are beginning to condensate again. It’s been a long trip, it’s been an emotional decathlon, and I’m toast.

But even as I’m trying to secure a bootleg signal in my mom’s living room to post these last two stories, I’m thinking about the Buj. It’s still there. It’s still going to wake up in a few hours even though we’re across the ocean. And our friends are going to keep spending themselves on behalf of it. It seems wrong to hope that you’re missed. But I do. Maybe because I just hope my own lament is reciprocated. Maybe it’s pure narcissism. But it’s sad to imagine Buja without me in it.

But that will have to be the dull ache in my spirit for the next few days. Because the hours of goodbye are over for a while. I’ve got a big week of hellos ahead. Off to bed. Goodnight.

1:45 Chicago Time, 2:45 Fort Wayne Time

Trina and Karri and I talked about this moment in the car on the way to the airport in Buj. Trina said that, no matter what her current opinions about our country, there was always this surge of gratitude and joy when the customs agent says those words. I didn’t know until today. But it feels pretty good.

Eight and a half hours on the plane from Brussels with my own private screen. For a movie junkie such as myself, no better way to pass the flight. I put some time in on other efforts, but come on. It’s a little screen built into the back of the seat in front of you! You could play Tetris with the remote built into the arm of your chair! Ridiculous. I’m flying over ice floes in Northeastern Canada and trying to squeeze the T piece into the space created by the oddly placed Z piece. What kind of bizarre world do we live in?

For my friends still in the Buj, you’ll appreciate this one. We land in Chicago and the fasten seat belt sign turns off. Everyone stands and collects their belongings, but there is no pushing. There is no climbing over seats. There is no unnecessary contact. We’re in the back of the plane and everyone is well aware that they are going to get their turn. Then we notice the gentleman behind us.

This gentleman in his sixties, maybe seventies, is dressed in a bright blue patterned dashiki and (how can I say this tactfully?) smells African. Like the cabs I would take every morning or the hugs from my dear Burundian friends that only lasted as long as they did because my love elongated my sensory endurance. He is clearly unenthused at the prospect of waiting for the plane to disembark. He has already posted up behind Karri, arm outstretched and boxing me out from entering the aisle in front of him, and is shifting from side to side, seeing if there’s an alternate route. Then the opposite aisle begins to clear out. This is more than he can bear. He wedges himself between Karri and the aisle adjacent to her, then excuses himself (AFTER this maneuver, mind you) and wriggles the rest of the way so that he can join the free flowing traffic. Karri and I looked at each other. It’s refreshing to know that here we are, on American soil once more, but some things just don’t change. Sorry if that anecdote goes over some heads, but that one goes out to my fellow fighters in the battle of the visa lines. Cheers, guys, and know that we’re still fighting the good fight here in the West.

One last jump to the homeland, and then we’re done. The chapter of our travels to Buja and back will end where it started. Our parents will be right where we left them, like they never left. I’ll have gained a drum, a goatee, and a slimmer waist. And then we’ll go… home? I guess so. But we left a little bit of home back there when Selius shut the gate the last time, a little bit when we left the arms of our friends in the airport, a little bit when our feet hit that staircase and left the ground. And there’s a little bit of home in that Philly apartment, a little bit traipsing around the globe with our Eastern friends. Maybe that means home just gets a little bigger, but the emptiness I feel by being separated from those people, those places makes me think that they are pieces of home, broken off the whole. And while I’ll never be depleted of home, I’ll always feel the phantom limbs that can never be replaced.

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

6:30am Brussels time, 11:30pm Fort Wayne time

I don’t sleep well on planes. I think everyone who designs transport is shorter than 6 feet tall. But Brussels air tries hard to make you comfortable. Good food, nice blankets. I look longingly at the curtain to first class and the extra-reclining chairs with ample leg room and rub my knees.

I’m greeted by what appears to be the African version of Total Request Live on the screens at the front of the cabin. Women from Ivory Coast, Guinea, Senegal sway silently back and forth to the drone of the engines and the stirring of the cabin crew. If you’ve never been to Africa, then African music videos are probably just a glimpse into the past of video editing, with producers who don’t know better than to use whatever stock transition effects are available on the software they’re using. The four-corner split and spin. The page-turn from the left. The page-turn from the right. The spinning block. But when you’ve been to Africa, you see something a bit more. You see this familiar desire to be Western while slightly resenting it at the same time. The ladies amble out of a sports car, but the man is wearing a dashiki. The dancing still holds quite a bit of booty shaking, while retaining the swaying arm movements of their days in the choirs of their youth.

It’s familiar because you see this tension on the streets every day. Love 50 Cent, resent the West’s money. Love Obama, resent the US foreign policy. Love Dolly Parton (don’t ask me, but everyone does), resent the imposition of Western cultures and values. I can’t blame them. I live in that tension every day. I’m simultaneously someone abundantly comfortable in the West and annoyed and critical of it. It’s the real tension I’m wrestling with this morning. We’re about to land in Brussels. Who am I now? On the other side of these eight months, will that tension be tilted to one side or another? I have three entries to post. Will I be upset if I can’t connect to the internet? Do I deserve it? Is all that stuff in my suitcase just relics of an extended vacation into development-land? I’m about to set foot into the land of automatic soap dispensers. Who am I?

9:45pm Nairobi Time, 2:45pm Fort Wayne Time

I’m not sure why I don’t cry much. People say that you’re not in touch with yourself; your heart is hard if you can’t cry. I don’t think I’m out of touch or steely, but it’s just not something I do a lot of. Admittedly, I probably said less to our friends in the airport than I wanted to because of the softball sized lump in my throat, and rather than pushing through it to the inevitable choke and sniff, I cut myself off and gave a knowing nod. Does that make me a coward for not wanting to cry? I don’t know. But I got that same lump in my throat when we made that short walk across the tarmac and boarded the plane. It felt like saying goodbye to one more friend.

7:30pm Buja Time, 1:30pm Fort Wayne Time

I’m in the terminal of Bujumbura airport, reflecting on the massive emotional hairball that was the last 2 hours.

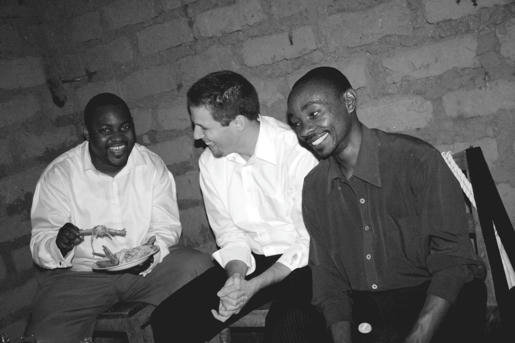

Our friend Paulin arrived first, bringing greetings from his family. He is an amazing, promising, enterprising, faithful young man with whom Karri and I have had the great pleasure of spending time. We sat with him, reflecting on the end of term and his hopes for the next year. Next came Samuel and David, the twins from our youth group and worship team, and two of the most affectionate, dear young men I’ve had the pleasure of working with here. I tried to draw a map of the States and explain where Fort Wayne was. It’s always amusing to watch Burundians who have never considered the size of the US realize how large our country actually is. Plenty of tongue clucking and whistling ensues. I’ll demonstrate for you upon request.

Then came Brandon, my fellow spiritual traveler and one of my closest friends here. He corrected my poor Canadian geography, and we discussed the books we’re reading. Finally, Trina came with the truck. The guys sprang into action, ferrying our luggage from the living room to the vehicles. A light rain marked our departure, and it felt slightly fitting. En route, we discussed with Trina the emotional sand trap of making friends in a context like this. Everyone’s leaving. It becomes easy to guard your heart and stay closed off. If you’re reading this, Trina, I’m abundantly thankful that your heart opened for us.

We arrived at the airport simultaneously with Isaac, Michelle, and Meg. These three, who along with Tyler made our community complete, have become fast friends to Karri and I. Michelle, while only here a few short months with many more to come, has proven to be inspirational and steadfast, and a gift to us. Meg came a few weeks after us, and as I said to her in a tearful embrace, brought us more joy than anyone we met here in Burundi. Isaac, however, was with us on the plane from Brussels. He’s been there from the beginning. And if I didn’t say it there, I’ll say it now. You’re an unbelievable person, Isaac, and we love you immensely.

All those emotions, all those remembrances, all those embraces, then through the looking glass and into the world of international travel. Checked baggage – no problem. But we’ve got a guitar and a drum to carry on. We thought we could get away with it. But first the drum got vetoed. $150. Then the guitar got vetoed. We fought, we persuaded. Our friend Noe from Turame came to see us off and advocated on our behalf. A woman who came to my music classes and works at the airport, Mirelle, won top marks in my book for her efforts. To no avail. $150. … On the upside, we don’t have to carry the instruments around the airport. A few people who have just said emotional goodbyes aren’t in the best psychological state to handle arguing over international baggage restrictions in French. C’est la vie.

Boarding. Goodbye, Burundi. I think we’ll see each other again.

3pm Buja Time, 9am Fort Wayne Time

It’s been a slow, lazy afternoon, and we’re only two hours away from departing for the airport. It’s difficult to describe the physical sensations I’m feeling. The closest thing I can associate is the feeling of nervousness before a performance. I guess nostalgia feels like butterflies. Or maybe I just know this is the long stretch of anticipation before having to say goodbye to the friends we’ve been closest to here. They’re all coming to the airport with us, and there’s going to be a moment in front of the terminal. There’s going to be a moment when we have to look one another in the eyes. It’s that moment that is causing my stomach to flutter, I think.

I’ve been pacing a lot this afternoon. Mainly because the power has been off all day, and once my computer battery died, I couldn’t write my thoughts. I pace when I’m bored, and it drives Karri crazy sometimes. I think I just like feeling like I’m going somewhere. I’m not very good at sitting still, or focusing wholly on one thing, and pacing gives me the sensation of motion without the nasty auxiliary of purpose. But today, I’ve got plenty to think about: what we’ve been through, where we’re going, how we’re going to get there. Where is Japan going to go now? How will the new tenant treat Selius? Will we really keep in touch with our friends, or will they become the people who you run into by chance years later and have to decide if you’re going to ignore or not because you used to be extremely close and aren’t anymore, which makes it more awkward than normal. And where do those little ants end up after they’re done scavenging the bit of pizza crust and traversing the impromptu highway their relatives have created?

So I pace.

9am Buja Time, 3am Fort Wayne Time

Just finished packing. No matter how many times I do it, it’s always odd to see my stuff in suitcases. Feels like you’ve wrapped your life up in boxes and bags. I know your stuff isn’t your life, but it exists as a kind of symbol. There’s no denying what it means when you pack the shirt you’ve never worn, or find the most effective way to roll your ties. Those are not normal things to do.

Our kitchen table is cluttered with things we’re giving away. Some things, like spare shaving cream, we just don’t care to pack. Some things we’re giving to people. The bed sheets go to Jean Baptiste’s orphanage in Bubanza. The external modem goes to Michelle. The phone goes to Selius, our guard, whose pregnant wife lives in Kayanza a few hours away while he works with us in the city. He doesn’t know that he’s getting a phone yet. I wonder what he’ll think. I can only assume, because he speaks no English or French, and is a bit of a soft-spoken man anyways. But he’s a great worker, smiles a lot, and is staying on with the house for the next tenant. So his job situation is ok. We worked hard to make sure of that.

The voices of the kids in the schools next door are drifting over the walls of the compound. Shouts, repeated lessons, laughs, taunts, all in this language I’ve heard every day but understand nearly nothing of. Sometimes, while standing outside of the gate, the kids would play this game of inter-language peek-a-boo. A group of ten of so would notice us standing in the street. The boldest would try his or her hand at their most recent French lesson. “Bonjour!” If we didn’t respond, she’d simply try again. “Bonjour!” When we’d finally turn and respond in kind, the group would squeal and pivot and jump and run in the unison of a school of fish, until someone else in the group decided to try it himself. “Bonjour!” Response, squeal, next contestant.

Karri’s organizing the money we’re leaving behind, bonuses for Japan and Selius, tuition for a friend of ours who is going to a tech school next year, and extra Burundian francs to sell off to our friends. We’re bringing home a few of the bills just to show people and have as souveniers. Of course, we’re bringing back nice, clean bills, but they will hardly be a clear indication of the norm. Most bills, especially in the middle to lower denominations, are soiled and blackened beyond recognition by being rolled, palmed, passed, and crammed into dirty pockets. It’s a strange practice, keeping money. I feel like there would be few things that could feel more familiar, more indicative of our months here than those pieces of paper. I handled it every day. I worried about it getting stolen. I bargained with cab drivers to save it. People I didn’t know asked me for it. People I did know asked me for it. Those won’t be the memories that last, the momentous things that will be repeated ad nauseum for the next few weeks. But if I want to think about the steady stream of days that run into each other that tend to formulate the bulk of your time and the minority of your description, I’ll find it in the smell of those bills.

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

6:00am Buja Time, 12:00am Fort Wayne Time

I rumble out of bed for the last time, untucking the mosquito net and trying to slide off the corner of the bed without waking my wife. I’ve been waking up earlier these days. Can’t seem to sleep past six. I head over to the coffee pot to get the daily brew started. No power. Figures. It’ll kick on in an hour or two. It’ll be strange to live in a place where the use of candles isn’t ubiquitous and you don’t have to try to finish your movie before 10pm because the electricity “leaves” (as you would say in Kirundi) every night at that time lately. I stroll over to the couch. Our neighbor has a rooster that has been crowing mercilessly every morning at just that hour when you have the delicious option of rolling over and getting that extra ten minutes. We’ve fantasized about exercising our inner Colonel Sanders. This morning he’s quiet. Maybe someone told him we were leaving.

There’s a rap on the gate. Selius, our guard, walks past the window to let our cook, Emmanuel (who asks that we call him Japan for reasons that are less PC than I’d prefer), into the compound. I live on a compound. This is my last day of life behind a gate. People who live behind gates in the West usually have Beamers or gardeners. I doubt I’ll ever be one of those people. But here, you accept life behind a gate. You accept a lot of things. You accept mosquito nets. You accept power outages. You accept roosters. How long will it take before I feel entitled again? Before I decide that the world owes me air conditioning and fast service at a restaurant?

Japan comes into the living room and says, “Good morning.” His English is good, not as good as his brother’s, but we understand each other well. I hear a little more in his greeting this morning. The tone of his voice says, “Yeah. This is it, isn’t it?” For me, I’m off to the States, a car, a bank account, a garage full of stuff. For him, this is the last day of his job. Best I can tell, he doesn’t have another one yet. Karri wrote him a letter of recommendation yesterday, and we’re going to give him a little extra money to help him out, but it’s tough to find a job like this. Working for a muzungu is a bit of a coup, and there’s always the fear that your next job (if you find one) won’t be nearly as good. Japan wants to get married. Japan wants to build a house. Japan wants to start his own business. I hope he finds another job.

Karri’s up. I know it’s going to be an emotional day, and so does she. I can hear it in her voice. Maybe the power will kick on soon, and I can make her some coffee.

Monday, April 20, 2009

The Fund-Raiser – Part IV: The Western Pastor

Now, my family and friends know that I struggle with many things, but speaking loudly is not one of them. I trained my lungs to sustain prolonged volumes while I was still in the nursery of my church. I was delicately nicknamed “Screamin’ Jim.” It’s difficult to think about my mother in my formative years without the words, “Inside voices, honey,” being far from her lips. My beautiful wife still turns to me at times and says, “You do realize I’m standing right next to you, right?” So when it comes time to sing, speak, or do anything involving the vocal mechanism, I am rarely difficult to hear. But I’m comfortable when I’m loud, and sometimes it’s a gift. So I when I stood to begin the teaching, I felt no reservations about my voice being adequate to fill the room. That’s when a microphone was pressed into my hand.

This brings me to one of my biggest frustrations with your normal, run-of-the-mill Burundian church. These are beautiful communities of believers, and I can only hope you will experience the sound of fifty naked Burundian voices and a paint can drum giving praise in your lifetime. Yet every single community I've encountered believes that what it is really missing, what, when lacking, is limiting the movement of the Spirit more than anything else in their worship, is a sound system. That’s right. A church of ten people that meets in a living room would still look at each other and say, “Wow. If only we had microphones, we could really see the Lord move.” I’ve been in church services where the worship was just stunning, only to realize that, the whole time, two guys had been trying to get the generator to work, and once they had, the snap-crackle-pop of the speakers came alive and all that raw sound was drowned out by a plugged-in, out of tune bass guitar and a synthesizer, using the most obnoxious horn sound it could muster and propelled by the internal drum machine. Never mind the REAL drum they already had, nothing beats the tinny, genre-specific groove that only Yamaha can produce. It just kills me, but I suppose I come from a place where those things are common, and the denial of them is postmodern-trendy. But still… come on.

But the Lord smiled upon me, and but three minutes into my talk, the generator died, and the squawky speakers that made everything sound like it was coming out of an outdated transistor radio fell silent once more. I quietly fist-pumped the air and cranked the old internal volume knob up to eleven. Now, I am loud, but I am nowhere near as loud as my fellow Burundian pastors. Apparently, spiritual things cannot be spoken of in anything less than what could be called a bellow. But I couldn’t very well accommodate this, especially that day. I had made a bit of an underestimation.

You see, the last time Jean Baptiste invited me to speak to his community, I over-prepared. I brought a teaching full of history and analysis, and found myself speaking to a living room of ten to twelve uneducated men and women who just wanted to know that God loved them. So when my friend invited me to speak again, I was ready. I prepped a talk about the Spirit of God being like the breath we breathe, and that “the Spirit calls to our Spirit that we are God’s children.” (Romans 8:16) It was a quiet talk meant for the dear people I had met once before. But here I was, in the middle of one of the loudest, most crowded rooms I had seen, and everything spoken to that point was easily on the “bellow” setting. What can you do? So I gave my talk. God loves you. Right where you are, exactly the person you are right now, God loves you. I didn’t bellow. I probably didn’t even hit eleven, if I was honest. But I tried to catch every eye in that room.

There are a lot of things you can say as a pastor, and hopefully most of them are true, kingdom-filled things that are necessary to the disciple-making ministry you are called to. But I have found no higher calling than catching someone’s eyes when they are really looking, their ears when they are tuned in just right, and saying, “God loves you.” Here I was, in a room full of people who would never see my country, maybe never leave their own. They probably didn’t even own their own Bible, much less spend much time pondering the cultural context of the Pauline epistles. Lots of pastors (and I, very often) use their pulpit to self-aggrandize, to flex their exegetical muscles, and reassert their place at the top of the spiritual food chain. I think sometimes we forget that the simplest truths are the most life-changing. Grace is still amazing. Joy is still contagious. Faith can still move mountains. Hope still springs eternal. Peace still flows like a river. And love? Love can still change the world.

Karri and I left soon after I said “Amen.” The celebration kept going, though. And the fund-raiser for Jean Baptiste’s church started that beautiful community on its way to a permanent place to stay. I wish they embraced a bit more the truth that God is much more comfortable in tents and wildernesses than temples (and that sometimes sound systems kill the mood), but I know it’s important to have a place to call sanctuary. And the things I saw there in that classroom, the potpourri of sights and sounds, of customs and theologies, of light and dark, of hope and joy, are what make the story real to me. It’s not a perfect church, but no church is. Surely, though, the Lord was in that place. And surely the Lord is always at work. May we have eyes to see and ears to hear. May we remember that generosity is the heart of God, that joy sounds like thump-CLANK-CLANK, that love wears a towel and washes unshod feet, and that sometimes, the truest thing we can know is that God loves us.

Friday, April 10, 2009

Celebrating Palm Sunday in Bubanza

Last Sunday (Palm Sunday) Jim and I were invited to two churches - in Kanyosha and Bubanza - by our friend Jean Baptist, so that we could share in worship with them and Jim could teach. The following are photos from our time in the afternoon with the Bubanza congregation.

Bubanza Landscape: The flat landscape is lush with vegetation and fertile for rice fields and other crops.

Driving into the dense vegetation far off of any 'main road' the taxi pulled up and parked in front of a small church and mud brick buildings. We were immediately greeted by the glowing faces of children anticipating our arrival.

This is a photo of the church congregation. However, before we were more than one song into worship, an incredible rainstorm came crashing down, suddenly ripping off the plastic tarp over the roof, washing down rivers of mud onto the congregation, covering Jim and Jean Baptist’s white shirted backs. Consequently, we were herded into a tiny room inside the mud brick building.

However, mud didn’t stop the worship. It continued outside in the rain by a few committed members and then was transported into the small room. At one point I stood in the doorway of the room, peering outside, until I realized the water dripping down on me at the entrance was actually mud. The small building was melting onto my skin and clothes because it was made from unfired mud bricks. I began to wonder how often they had to repair this home.

Once the rain stopped we returned outside. Everyone filed into the tightly cramped benches and listened as Jim began to teach, with our friend Jean Baptist translating at his side.

After the teaching they led Jim and I and Jean Baptist back into the small room, where they generously fed us the best of their veggies, potatoes and chicken.

The province of Bubanza was the hot bed of rebel fighting during the war. The evidence of this can be seen here, where the church has taken in over seventy orphans and has a congregation filled with widows struggling to care for their families. Following our food, they escorted in a large group of orphans and some widows. Suddenly we were standing face to face with a line of timid eyes looking back at us, none of us speaking. However, the tension was soon broken as we called them closer to us and they finally broke out in a call and response worship song, clapping and stomping their feet. Smiles were infectious.

Jim was asked to share a few words with them, which is again, a difficult request. We were slightly uncomfortable with the blatant characterization of these individuals as simply "orphans" and "widows" - seeming to reduce them to two dimensions. However, the compassion and commitment to the 'least of these' as demonstrated by this church and our friend Jean Baptist assuage any concern that they are treated less than creations of the Divine. Jim offered the best words he had - reminding them of how much they are each loved by God. After taking numerous photographs, I told them I would take their faces home with me to share with my mom, family and friends, praying for and remembering them.

Jim and I were both overwhelmed. We were overwhelmed with their joy, their worship, their compassionate and generous hearts, the struggles they face. I also found myself overwhelmed with the spirit of God - feeling in a very tangible way that these children were deeply loved and cherished by a God I understand more after having looked into their faces. You find that when you encounter the Divine you are often at a loss for words.

As we finally stood to leave, a young brave boy asked something of me in Kirundi. My poor Kirundi skills being what they are, I had no idea what he said. Finally JB said he was asking for a pen. I pulled one out of my purse and handed it over - to the slight panic of JB, who quickly led me out of the room before I was mobbed with pen requests. Ah, he only wanted a pen...

As we climbed back into the taxi, the smiles and waves swarmed us again, more brazen this time, full of energy and mischief and life.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

The Fund-Raiser – Part III: The Shod and the Shoeless

This deserves a bit of exposition, because there is a good deal of misunderstanding between cultures in this situation. Let me share another story as an example. Karri and I went to see a Burundian friend graduate from his Bible school a few weeks ago. We weren’t speaking or doing anything other than attending as friends of the graduate. As we arrived, the head of the program greeted us and ushered us to the front of the room. We explained, as politely as we could, that we wanted to sit with the rest of the friends and family. The gentleman looked slightly confused and urged us again to take one of the seats of honor. We then explained that we wished to take photos and sitting in the front would prevent us from doing so. He gave an understanding and relieved nod, and let us seat ourselves.

From the Westerner’s perspective, there is an awkward tension in constantly being seated in places of honor. Most of the expats I know in Burundi are here to serve the Burundian people, to stand beside them and give them dignity and value. When we are paraded to the front of a gathering, we feel separated, scrutinized. We feel that we are being singled out for our status, our wealth, our education, at times even our skin color, and these distinctions carry negative connotations in our cultural framework. We don’t agree with elevating the rich above the poor, the educated over the non-educated, and the white over the non-white. So we fight against these distinctions on the battleground of the seating order. We cluck our tongues when asked to sit in the front, and refuse to participate in this discriminatory cultural practice.

But as we have processed this with our Burundian friends, they find our refusal to sit in front just as offensive. As I’ve said before, their customs of “Karibu,” of welcome, mandate that a guest receive the best the host can offer. This includes food, drink, seating, and anything else the host can provide. Receiving a guest is a tremendous honor for a community, and a guest who has traveled far to be with them especially so. When we refuse to accept this hospitality, we are ignoring their cultural practices and robbing them of the opportunity to honor their guests. So when Karri and I reframed our refusal to sit in the front of the graduation by indicating that we would be more comfortable and more accommodated by sitting where we could take pictures, the host immediately understood and accommodated our request.

It’s also quite common to be asked to stand and introduce yourself in a Burundian church, so if you have the chance to visit, be prepared to say a few words of greeting, no matter where you’re seated. There’s a standard portion of a Burundian church gathering where all guests are invited to stand and introduce themselves. Some churches do this for all guests, some only for more “important” guests. This brings me to the caveat in my explanation. I wanted to make clear that there is some legitimate cultural value in the practice of seating dignitaries and important people before I talked about the dark side of that practice.

Burundians deeply value authority and title. While this is appropriate in the sense of respect, it becomes a source of conflict and exploitation at times. Many will fight (sometimes dirty) to obtain and to keep authority, and once they get it, they wield it with vigor. And the community has a need for these roles to be defined, who is higher, and who is lower, so they encourage these distinctions to be drawn. Some westerners are seated in places of honor because they are seen as above everyone else. (That or the community wants them to be seen, that it might bring honor to their church or their pastor in the eyes of others.) This perpetuates a thinking that has been in place since colonialism, that come people are higher than others, that might makes right, that money means power, and power should be elevated. It perpetuates a thinking that the normal Burundian is low, unimportant, like sheep without a shepherd. And many Burundians see this classification of lowliness as a security blanket. They don’t have to think for themselves or stand up for themselves. They’re slow and unimportant, so they leave those things to the people in the seats of honor.

Now, the one place where this should be turned on its head is the church of Jesus Christ. We follow a Rabbi who reached out to the lowest, most marginalized people around him. He touched lepers, spoke kind words to prostitutes, redeemed tax collectors, and exalted little children. He talked about foxes having holes and birds having nests, but not having anywhere himself to lay his head. He took off his robe, wrapped a towel around his waist, and washed the feet of the people he was leading. This servant king then spoke these words,

“Now that I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also should wash one another’s feet. I have set you an example that you should do as I have done for you. Very truly I tell you, servants are not greater than their master, nor are messengers greater than the one who sent them.” (John 13:14-17)

The servants of this Jesus should be the ones who wash the feet of their neighbor. They are ones who know that the great must be like the servants of all, willing to shed their garments and dirty their hands for the people they lead. Jesus’ way is the path of descent, the upside-down Kingdom, where the one in the seat of honor is the least among you.

As I stood to introduce myself, I looked out at the people squeezed into the school desks. Shirts with holes, hand-me-downs from the affluent West, covered undernourished and thinning torsos. And I’m sure if I could see and count their feet, I would not count the same number of shoes, maybe not even half as many. Then I turned to look at the well-dressed gentlemen who had already stood. Over the top of their copious bellies, they wore suits with the sheen of a televangelist, tags bearing Western name-brands still sewn into the sleeves of the jackets like badges of merit. And one each foot was a well-polished, patent leather dress shoe.

I don’t know these pastors personally, so I’m not sure how they lead their communities. I do know many pastors here who simply joined the ministry so they could wear suits like that while they told the shoeless people in front of them how to live their lives. As I sat back down again, I wondered to myself, would they take off those shiny, tagged jackets, scuff their European shoes, and wash one of those unshod feet in front of them? Would I?